There’s no stopping electric vehicles

Demand for battery-powered electric vehicles is expected to soar over the next 20 years as governments impose emissions restrictions, battery prices decline, and businesses and consumers opt for energy-efficient transport options.

While analysts concede electric vehicle take-up has been slow to date, with many consumers apparently deterred by the lack of supporting infrastructure and relatively high prices for EVs, global consultancy BloombergNEF believes that almost 60 per cent of new passenger vehicle sales in 2040 will be either plug-in hybrid or batterypowered electric vehicles.

Deloitte analysts say there has been a “sea change in attitudes” to electric vehicles.

“After years of being viewed as a fringe technology, the battery electric vehicle [BEV] market is finally nearing a tipping point,” Deloitte says, noting “positive change in customer perceptions, technological advancements and greater intervention from governments are combining to focus attention on BEV adoption”.

The tipping point, according to Deloitte, will be 2022 when, by its reckoning, the cost of owning a battery-powered electric vehicle will be “on a par” with internal combustion vehicles.

Electric vehicles currently represent less than one per cent of the estimated one billion vehicles on the road globally, according to BloombergNEF, and 2.2 per cent of new cars sales in the first 10 months of 2019.

But some regional markets are progressing faster than others. Britain announced in mid-2017 that it would ban sales of vehicles using petrol or diesel by 2040, following a similar move by France. India’s goal is for 30 per cent of all car sales to be electric by 2030, winding back an earlier, less realistic target of 100 per cent.

As well, the Chinese government recently announced it would shift from subsidising electric vehicle makers to enforcing sales quotas. It wants 25 per cent of all light vehicle sales in 2025 to be electric, a move that puts pressure on international car makers to step up production of their EV models.

Australia, however, does not yet have a national policy or strategy on electric vehicles, despite the strong recommendations of a Senate select committee in January for the government to “prioritise” the uptake of electric vehicles by governments, businesses and consumers.

Progress so far has been piecemeal, driven by fleet-purchases by individual councils or businesses. Yet, as the Electric Vehicle Council has pointed out, companies are proving innovative in design and technology, Australia has significant reserves of lithium for battery production, and the nation could create many jobs in this industry.

“The global electrification of transport provides a massive opportunity for Australian businesses to generate local, green and highly skilled jobs,” the EVC said its recent report. In California, where public transport options are limited, and cars rule, hybrid and electric vehicles represented 13 per cent of all new-vehicle registrations in the six months to June. Meanwhile, the world’s biggest car maker, the German group Volkswagen, which owns brands including Audi, Porsche, Skoda and Lamborghini, is investing heavily in electric vehicle production,

committing 30 billion euros ($A48.9 billion) to electric vehicle technology and manufacturing. It intends expanding its current range of six electric models to at least 50 and will manufacture EVs in Europe, Asia and in the US from its facility at Chattanooga, Tennessee.

As global car manufacturers switch their investment strategy to electric vehicles, there are profound ramifications for many other sectors.

Companies that make lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles are accelerating production and building vast new facilities. Prices for lithium-ion batteries have fallen about 85 per cent since 2010, according to BloombergNEF, while the technology going into batteries is fast improving.

China currently dominates world production of lithium-ion batteries with facilities that potentially yield about 73 per cent of global manufacturing capacity, and it plans to build at least 40 more. in a series of so-called gigafactories: the first is near Reno, Nevada; the second at Buffalo in New York state; and the third, in Shanghai, is about to generate its first commercial production. A fourth gigafactory is likely near Berlin.

Besides passenger cars, one of the biggest growth markets for the electric vehicle industry is expected to be light commercial trucks, delivery vans, sweepers and street scrubbing units, airport luggage carriers, and a host of automated fleets that do not require drivers.

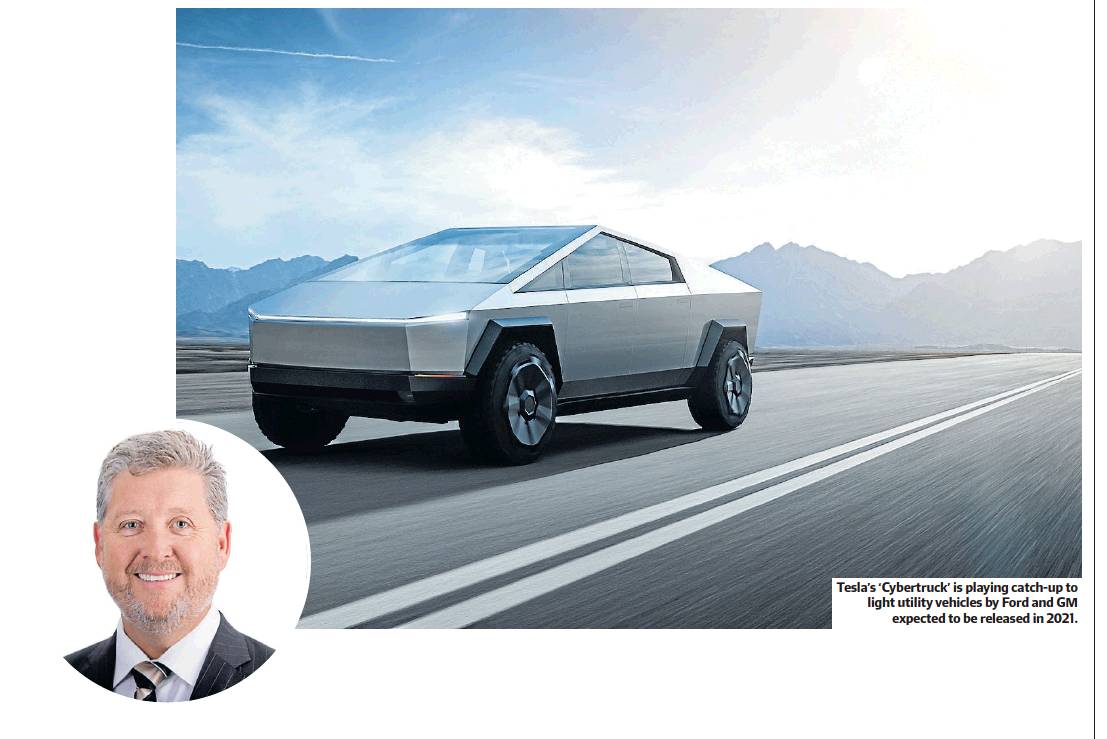

Tesla might have gained attention when it launched its futuristic, Darth Vader-like Cybertruck recently, but Ford will produce a more conventional take with its electric light truck (or utility) in 2021 – about the same time GM brings its version to the market.

Phil St Baker, the managing director of Novonix, which makes graphite anodes for lithium-ion batteries, suggests growth for automated trucks and light commercial vehicles may take the world by surprise.

Amazon, for example, has already placed an order for 100,000 electric delivery vehicles from Michigan electric vehicle manufacturer Rivian.

“It is mind-blowing where all that is going,” he said. “Going full-electric in trucks is coming very soon.”

US car makers that are seeking to curb their reliance on China, de-risk their businesses and win credit from the nationalistic administration of President Trump are forging deals to obtain lithium-ion batteries and battery components from US-based suppliers.

Tesla and Panasonic, for example, are partners