Secret life of bats

They’re maligned as fruit thieves, disease carriers and even friends of Dracula. But there’s a lot more to these mysterious creatures than

meets the eye. Simone Fox Koob explains.

It’s dusk and, in the moments after the sun dips below the skyline, the city’s night flyers flood the sky. In its own way, the nightly aerial show is a majestic sight. But for many it’s also a mystery. Where do these creatures come from, and where are they going?

There are thought to be about 780,000 grey-headed flying foxes in more than 100 camps across Australia. A threatened species because of dwindling habitats, they have been further battered by recent heatwaves that have seen them drop dead, by the hundreds, out of trees from Melbourne to Cairns.

Flying foxes occupy the evershrinking forests and woodlands along the east coast, and in Sydney they particularly like to hang out in Centennial Park. Bats have been moved on from the lush city botanic gardens of both Melbourne and Sydney in recent years. But none of them stay put in any one spot. These mammals are nomadic and operate in one single, mobile population, with individuals moving up and down the coastal belt in waves.

WHERE DO BATS GO DURING THE DAY?

Look up into the towering branches of flying fox camps during the day and you will be greeted by a relatively serene sight. The camps are not permanent homes but are more like hostels, with a turnover thought to be roughly about 10 per cent every day. In these parkland hostels, you will find everything from mothers caring for newborns to travellers seeking a stopover to semi-permanent residents enjoying the local culinary scene.

The sizes of camps depend on what food is available in the area and the time of year – in summer, colonies are generally larger but it’s in autumn, the breeding season, that colonies can be the loudest and smelliest. About this time of year bat pups, born the year before, are weaned and females are ready to fall pregnant again. Amorous males start to advertise themselves with an oil that they rub onto branches to attract the opposite sex.

“The smell is musty,” says Parks Victoria bat ranger Stephen Brend. “If you imagine decomposing fruit, like in an orchard or fruity compost. The smell is from the male’s oils.’’

The twilight cacophony from the trees is also at its peak at this time of year. Juvenile bats, freshly weaned, are finding their places in the colony, says Brend. “They’re like rowdy teenagers on their own for the first time, on the edges of the colony, making noise.’’

Bats have few natural predators. Further north, the odd goanna and python may be partial to a bat; in Sydney it’s more likely ravens that will try to snatch a newborn, or owls and other raptors that may try to prey on a flying fox. So, during the day, hundreds of bats, hanging upside down, will snooze in the sunlight, attached to branches by their feet, which have a locking mechanism so they can hang effortlessly.

WHERE DO THEY FLY AT NIGHT?

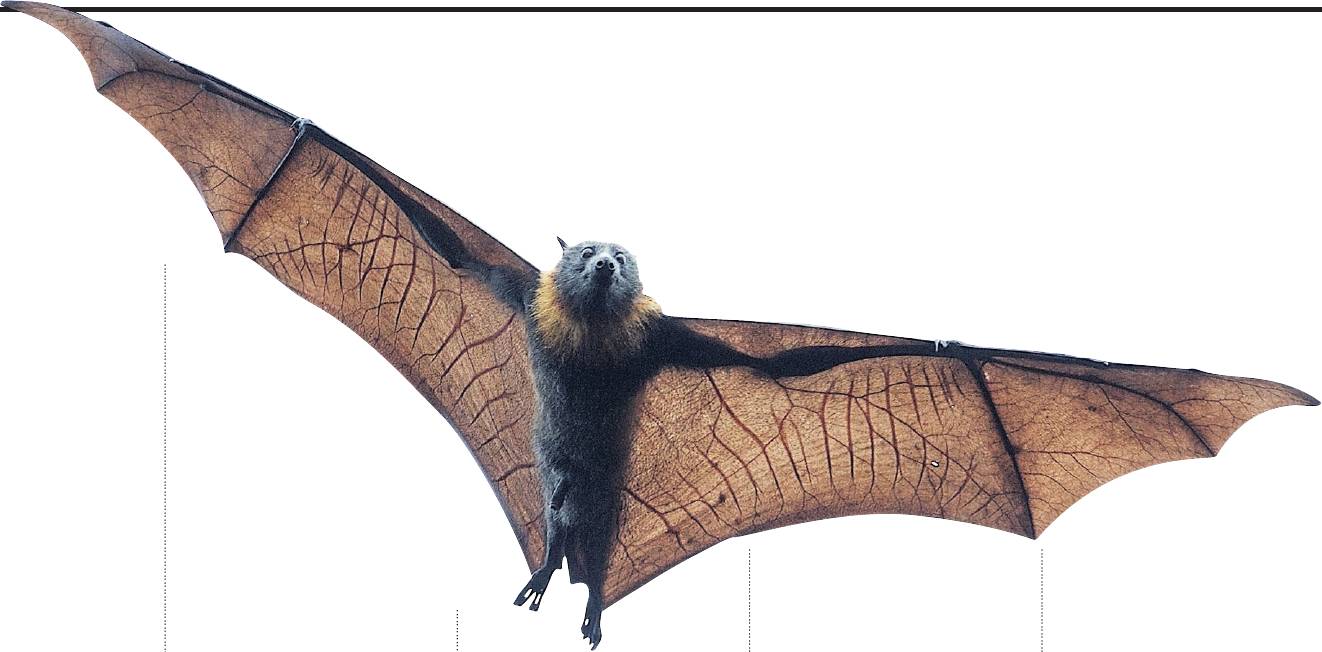

About 20 minutes after sunset they let go. Dropping from their branch, they use the momentum and flap their wings, which can span up to one metre and are made of soft, leathery skin.

Flying foxes take off en masse

– the collective nouns for bats are a cloud or a colony – initially flying together to find dinner.

In Sydney, residents of the inner east, in suburbs such as Paddington and Randwick, witness the evening fly-out. Gradually they disperse, splitting from the pack and flying solo or in small groups. They navigate using major waterways and highways. Large, glassy eyes work as an inbuilt GPS, highly adapted for both day and night vision and particularly suited to recognising colours at night.

“They fly about 20km/h, and their eyesight is like a cat. We think they follow roads and rivers,’’ says Brend.

WHAT THEY DO

Once they are away from the camp, the search for food begins. It’s flowers and blossoms, particularly eucalypts, that are their first choice for a meal. “Think of them as big nocturnal bees,” says Brend, “pollen and nectar is what they are after.”

They will also want several different types of food every night, meaning they will travel far – generally about 20 kilometres but

in some cases up to 40

kilometres – in one evening.If

they can’t get nectar or

pollen, they will find fruit.

And this is where they

can make enemies,

munching on fruit

crops or orchards in their search for dinner.

Figs are big on the menu, as are mulberries and in fact most softskinned fruits; the bats pluck the fruit and tear apart big pieces using a thumb claw and foot. To drink, they bellydive into waterways and then hang upside down, allowing the water to run off their fur as they lick it up. After a night spent flapping from one tree to the next, they return to camp just before dawn, with mothers the first to head back.

Bats creche their young, meaning when the babies get too heavy to carry after about six weeks, mothers will leave them together in the trees without supervision before returning to find their pup.

DO THEY DO MORE GOOD THAN HARM?

Flying foxes have been known to cause damage to commercial crops and orchards, public gardens and native vegetation since European settlement. It’s this type of destruction that gives bats a bad name.

“It’s really damage to commercial crops and backyard fruit trees which upsets people,” says Brend. He says there can also be concern about public gardens when bats start roosting in those trees, although the damage to local vegetation is minimal.

Governments and councils must delicately balance the interests of residents with those of bats. It’s important to remember that the vast movements of flying foxes makes them an integral part of the ecosystem. They play a major role in the regeneration of native hardwood forests by long-distance pollinating as they disperse seeds during their travels. A single flying fox can scatter up to 60,000 seeds in one night.

BUT DON’T THEY CARRY DISEASES?

There are perceptions that the flying fox is riddled with disease. They are indeed hosts for Hendra virus, which can be transferred to horses by bat saliva, and then from horses to humans; and the Australian bat lyssavirus, which can be caught from untreated bites or scratches and which has symptoms like rabies. Infection is extremely rare. Three people have died after being infected with the lyssavirus in Australia since 1996. Four people have died of Hendra virus since it was discovered in 1994, and some 90 horses have been infected in northern NSW and Queensland. “Very, very few bats have lyssavirus,” says Brend. “If you don’t touch the bats, you’re safe. It’s not in their wee or poo. If the bats are carrying the virus it’s in their saliva. A dog bite is more dangerous than a bat. The biggest misconception is that they are slightly sinister creatures of the night, friends of Dracula. But in fact they are social, communicating mammals.”

WHY ARE BATS A THREATENED SPECIES?

In the wild, flying foxes can live for about 15 years but they are being threatened by a range of factors. One of the biggest threats is habitat destruction; increasing conflict with people and extreme weather events are also hazards. Heatwaves have led to mass deaths. Lawrence Pope, the president of Friends of Bats and Bushcare, says heat has the same effect on flying foxes as humans. When their core temperature rises, bats become disorientated and can collapse and die. “The species is feeling the effects of climate change,” Pope says. “Climate projections show these weather events will get more and more frequent and severe. I don’t know if we can save this species. Some scientists think it will be extinct by 2050.”