The high price Turnbull paid to become PM

ENDGAME Part 2

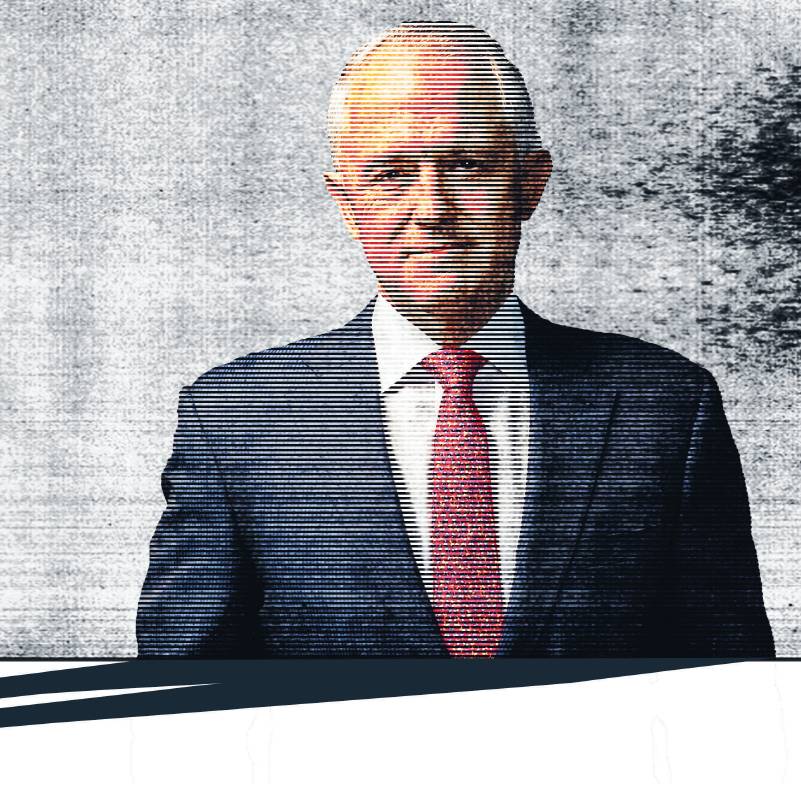

Malcolm Turnbull started his time at the top shackled to the very policies voters thought had been discarded with Tony Abbott, writes Peter Hartcher.

Malcolm Turnbull was ready to be sworn in as prime minister. He had beaten Tony Abbott for the Liberal leadership and now he needed to make the 10-minute drive to see the Governor-General. But he had hit a snag.

It was called the Nationals. Without their country cousins and Coalition partner, the Liberals didn’t have a majority in the House of Representatives. They couldn’t form government.

The Nats were driving a hard bargain. Turnbull was resisting. And parliamentary question time was looming.

Who would stand up in the prime minister’s position at the dispatch box when the clocked ticked 2pm? Abbott hadn’t tendered his resignation to Sir Peter Cosgrove.

So far as the constitution was concerned, he was still prime minister. But it was September 15, 2015, and the Liberals had voted Abbott out the night before.

Abbott’s timing was an inconvenience; the Nats were the obstacle. The leader of the Nationals at the time, Warren Truss, had pointedly reminded MPs the night before that ‘‘my Coalition agreement is with Tony Abbott’’. It was a personal pact, not a party one. It did not automatically transfer to the next Liberal leader.

Truss is a courtly, slightly fusty figure, yet he can be firm. His position was toughened by his deputy, the bare-knuckled Barnaby Joyce. In fact, Truss’ own leadership was under pressure. He had to demonstrate to his party that he could be tough on Turnbull.

The Nats were suspicious of Turnbull’s progressive instincts and his prime ministerial plans. As a senior Turnbull aide put it, ‘‘mostly they were suspicious about Malcolm bringing all the gays in and doing climate change’’.

They wanted to be sure that he would keep Abbott’s policies on these hottest of hot-button issues – no change to climate change policy, no change to same-sex marriage policy. Specifically, Turnbull had to pledge that he would keep to Abbott’s plan for a plebiscite on same-sex marriage.

The problem, of course, was that the Australian people were expecting Malcolm Turnbull to be what Malcolm Turnbull had always been – on these big issues, the exact opposite of Tony Abbott.

What none of the Australian electorate knew was that, to win the final votes he needed for the Liberal leadership, Turnbull had already promised some conservative MPs from Queensland that he wouldn’t alter Abbott’s policies.

And now the Nationals demanded that he put the pledge in writing. Otherwise, there would be no Coalition. Turnbull argued for more flexibility, especially on same-sex marriage, but the Nats weren’t yielding.

Turnbull already had one wrist cuffed by his promises to conservative Liberals. Now he was about to have the second wrist handcuffed immovably into a formal, written agreement with the Nats.

The negotiations between the two leaders started about 8am, face-toface, then broke off and resumed later over the phone. Even after Turnbull thought they had an agreement, Truss was still consulting his party, going through the text word by word.

As agonising hours ticked by, Christopher Pyne kept checking with Turnbull’s staff. ‘‘What the hell do we do about question time?’’

They decided to postpone to 2.30pm.

Abbott eventually gave his valedictory press conference starting about 12.40pm. Turnbull’s staff told reporters they were delaying the swearing-in ceremony out of courtesy to Abbott. In fact, they were sweating on the signed letter from Truss. Frantic calls were made. They didn’t yet have a Coalition.

‘‘I had no choice,’’ Turnbull complained to colleagues. He grudgingly went along with the Nats. He agreed to spend $10 billion on the inland rail freight line. He even agreed to a little extra something for Joyce – power over water policy was added to his portfolio of agriculture. Turnbull took water from a Liberal to give it to Joyce.

The Nats got everything they wanted. The signed letter from Truss finally reached Turnbull’s office about 1.15pm. The letter, true to custom, has never been published.

Abbott resigned to the Governor-General by email rather than in person – unorthodox but not unprecedented. Officials delivered the original by hand. Turnbull was sworn in to the prime ministership about 1.35pm.

The restraints he wore were not yet visible to the public, but the new leader was shackled to the very policies the Australian people thought had been discarded along with Abbott. As the political psychologist James Walter, of Monash University, put it: ‘‘He was tying his hands from the first.’’

Abbott had been deeply unpopular. The people thought that Turnbull had saved them from him. In truth, the Turnbull government was a policy cohabitation with Abbott. In his most incisive summation, Abbott said Turnbull was ‘‘in office, not in power’’.

At the time, the handful of Liberals who knew the situation agreed that Turnbull had had no choice but to yield. But some have since rued that fateful moment.

‘‘We shouldn’t have agreed’’, with the Nationals, ‘‘we should have pushed back’’, a leading member of the Liberal moderates faction Simon Birmingham, the Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment, for instance, has since told colleagues. ‘‘The high-risk approach – did the Nats have the guts to walk away from the Coalition?’’

Some of them were talking tough at the time. A Nationals senator and Joyce understudy, Matt Canavan, said, ‘‘I see no reason to rush into a Coalition agreement’’ even as it was being negotiated.

Other Nats urged their leaders to boycott the routine Coalition party room meeting with the Liberals that day. Why? To keep themselves apart and, implicitly, to threaten to stay apart. But Birmingham, who served as a key numbers man to Turnbull in his coup against Abbott, now believes that it would have been worth the risk of a Coalition crisis.

‘‘One of my greatest regrets was the conversation with Malcolm the morning after’’ the successful leadership challenge, Birmingham lamented to colleagues.

Sitting in Turnbull’s office of communications minister because the deposed Abbott had taken up residence in the Prime Minister’s suite – where Josh Frydenberg and Mathias Cormann supplied him with Scotch and other essentials for several days – Turnbull and Birmingham discussed the demands of the Nationals. ‘‘The Nats were playing a hard and heavy hand, and the call was to cop it, and deal with it later,’’ Birmingham observed to colleagues.

But it was never dealt with later, except on the Nats’ terms.

He saw the surrender on same-sex marriage as uniquely costly: ‘‘That issue, more than any other, gave strength to Labor’s narrative that Malcolm had capitulated to the Right. It didn’t hurt immediately, but the symbolic power was huge.’’

It never does hurt immediately to sell your soul, as Dr Faust would attest. The gain is always immediate, the full price redeemable later.

In Christopher Marlowe’s famous 16th-century version of the tale, Faust is given supernatural power to satisfy all his desires for 24 years. He merely needs to cut his arm for the blood to sign his pact with Lucifer. He airily dismisses the information that he will suffer pain in a hellish afterlife. It is only as the last hour expires that he comprehends his fate, as an angel of Lucifer opens the way to his doom: ‘‘Now, Faustus, let thine eyes with horror stare/into that vast perpetual torture-house.’’

Or as the Right’s Eric Abetz, a conservative Liberal senator and Abbott advocate, put it to colleagues: ‘‘Malcolm said he wanted to be prime minister by the age of 40, but when he turned 60 and he hadn’t made it, he decided that he’d do anything to get the job.

‘‘He sold everything he believed in, then later surreptitiously tried to take it all back.’’

What alternatives did Turnbull have? In retrospect, say his loyalists, he might have tried asking for permission to address the Nationals party room directly. He might have tried to ask the Nats that the samesex marriage policy be sorted out through debate in the Coalition party room, not laid down in a rigid agreement.

Or he might have used his tremendous early popularity to exert public pressure on the Nats. But none of this was attempted. The deal was done. It was now just a matter of time until Australian voters discovered the full implications. Emeritus professor James Walter said: ‘‘I remember saying, ‘Why the hell doesn’t he stare these guys down?’ He was extremely popular in the approach to the 2016 election. But he’d already made all these concessions.’’

It was, said Walter, ‘‘a Faustian bargain’’.

By the time the research firm Ipsos convened focus groups on politics for The Age in 2017, it had become very clear to ordinary voters that Turnbull no longer represented the progressive ideas for which he was known.

In 30 years in the public eye, he was most closely identified with action on climate change, legalisation of same-sex marriage and an Australian republic. After nearly two years as prime minister, uncommitted voters were thoroughly frustrated with him.

Said an older voter in western Sydney: ‘‘He just needs to grow, pardon me, balls.’’ A younger voter from Melbourne, reflecting a widely shared view, said: ‘‘If he just had the guts, the political will.’’ A woman from Melbourne said he needed to ‘‘just do something, like same-sex marriage’’, regardless of what you thought of the policy – ‘‘just do something’’.

There was also consensus on understanding that he had surrendered to the right wing of his government.

‘‘Everybody hates you, Malcolm,’’ Alan Jones, 2GB radio provocateur and Abbott ally, yelled down the phone in mid-2014, Turnbull related to friends at the time.

‘‘Everybody hates you!’’ And, with increasing intensity, a third time: ‘‘Everybody hates you!’’

It’s a call that Jones had no recollection of this week when asked about it. ‘‘This is fantasy; he’s trying to build a picture that I hate him and I’m conspiring against him,’’ said Jones. ‘‘I didn’t think he was important enough to bother.’’

Turnbull had agreed to be interviewed by Jones, famously abusive of guests who reject his reactionary populism. Turnbull was about a year out from becoming prime minister and hoping for a fair hearing. He took the precaution of calling Jones the night before their interview.

It didn’t help. But Turnbull now knew that Jones was not to be reconciled. And he took notes.

The Sydney radio host, an admirer of Abbott, opened the notorious interview the next morning on June 4, 2014, by demanding that the minister for communications pledge support to his leader.

‘‘Can I begin by asking you if you could say after me this? ‘As a senior member of the Abbott government, I want to say here I am totally supportive of the Abbott-Hockey strategy for budget repair.’’’

Turnbull’s rejoinder: ‘‘Alan, I am not going to take dictation from you.’’

This established the relationship between them that would prevail throughout Turnbull’s prime ministership. It was also representative of the relations between Turnbull and the wider pro-Abbott conservative media claque.

Ultimately he did take dictation, policy dictation, from conservatives in his own party as the price of winning the Liberal leadership, and from the Nationals as the price of forming a Coalition government.

Yet, for most of the conservatives in the Coalition, and among their media cheer squad, Turnbull could never be given any credit. He was, at best, a temporary vehicle who was tolerated in order to carry the Coalition to win the next election, but never embraced, never trusted. The electorate felt increasingly let down by him and the conservative faction detested him.

As Dr Faust might have told him, it was only a matter of time.

‘He sold everything he believed in.’

Eric Abetz

TOMORROW

Firebrand to fizzer: What was the point of the Turnbull government?