How Dutton swooped in from the shadows

ENDGAME Part 4

As Tony Abbott noisily set about destroying his nemesis, one of Malcolm Turnbull’s ministers was plotting his own rise, writes Peter Hartcher.

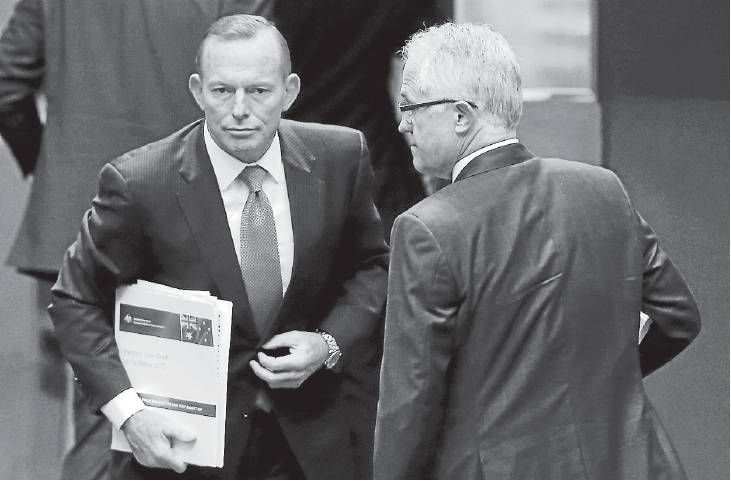

When Malcolm Turnbull told Tony Abbott there was no way he would ever allow him into his cabinet, it didn’t go down well.

‘‘Fair enough,’’ replied Abbott at their meeting in the Australian Club in Sydney after the 2016 election, specially brokered by a mutual friend to try to find a peace settlement between them.

‘‘You do your thing and I’ll do mine,’’ said Abbott. ‘‘And you have a lot more to lose than I do.’’

He set about destroying the leader of his party.

The prime minister had again tried to interest him in a diplomatic posting, but there was only one job Abbott would accept.

‘‘I put Malcolm in my cabinet, whatever my judgment about him as an individual, because he was a sufficiently senior politician,’’ Abbott says. ‘‘But Malcolm never reciprocated – that was his fundamental mistake.

‘‘The first duty of a party leader is to keep his party together. But you can’t keep your party together if you appear to have a personal grudge against some of your most senior members. You don’t want a cabinet full of sycophants.’’

Yet while Abbott’s project of vengeance dominated the public debate over the prime ministership for almost the entirety of Turnbull’s three years, inside the government it was a different story.

Abbott’s wrecking tactics cost him the respect and support of an ever-growing number of his colleagues. His visions of a glorious return to the prime ministership faded. This didn’t deter him. He only ever thought of a return to the leadership as a bonus. More important than recovering the prime ministership for himself was to wrench it away from Turnbull.

And as he threw himself noisily into the effort, a new challenger quietly built his strength.

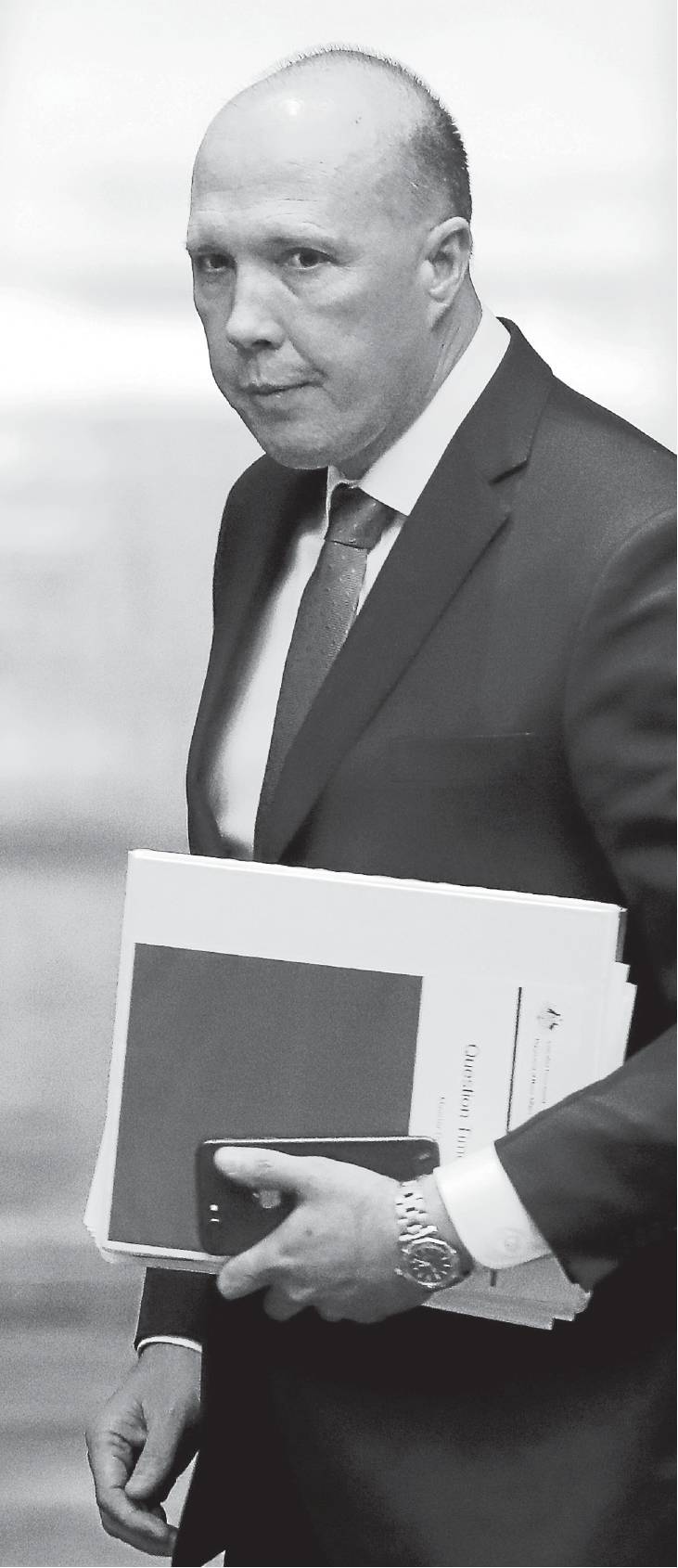

At his desk as immigration minister, Peter Dutton was feeling the constraints of his position. Quite literally.

Dutton prized the handsome, antique desk that he’d found – he believed it had once been John Howard’s. But Dutton is a big man and the desk was small. To sit at it properly, he needed to balance it on his knees. Bearing Howard’s mantle was no light affair, it appeared. Facing him on the wall opposite his desk was an enormous map of Australia and the world to its near north. This was a useful accessory for a minister anxious to track approaching boatloads of asylum seekers.

But with the restraining desk and the big, beckoning world beyond, surely it could be only a matter of time before Dutton dreamt of bigger things. And so it was.

For more than two years he was a close and loyal ally of Turnbull’s. When Brisbane-based Dutton, his wife Kirilly and their young boys visited Sydney during summer, Turnbull would invite the family to visit his harbourside home.

Dutton refused to help Abbott. He told his former leader that he shouldn’t try to bring down Turnbull, that ‘‘Malcolm is very capable of blowing himself up without any help from you’’.

The smarter game for Abbott would be to say nothing, allow Turnbull to fail on his own terms, and perhaps recover some of his previous support in the party. But Abbott was beyond logic, lost in a burning, visceral hatred of Turnbull.

Some outside observers claimed to be certain that Dutton was just a stalking horse for Abbott the whole time, one conservative aiding another against a progressive prime minister. The truth was more interesting. Soon after Abbott launched his full fury on the prime minister in the aftermath of the 2016 election, Dutton told him over dinner that he would not help him destabilise Turnbull, that it was Dutton’s best and wisest course to try for as long as possible to make the Turnbull government successful.

‘‘It wasn’t true that Peter was a stalking horse for me,’’ says Abbott. ‘‘He’s a friend of mine, I assume he always will be. He was an effective minister in my government and in Turnbull’s. I would talk to Dutts every month or two and we’d chat about things, but, to his great credit, he was a very loyal member of the Turnbull government.’’

In fact, Dutton had concluded that Abbott’s time had come and gone. It was now his opportunity to supplant Abbott and emerge as the leader of the conservatives and ultimately prime minister.

He played a patient, careful game. He would build his strength until his time came. Sometimes other conservatives would lose patience with Dutton and complain that he was too loyal, that he was propping up a leader they despised.

Dutton’s most dramatic rescue of Turnbull was over same-sex marriage. Turnbull was stuck. He’d pledged to implement the Abbott government policy of a plebiscite. But Labor and the crossbench combined to block parliamentary approval for any plebiscite.

The public demanded action on same-sex marriage, but Turnbull could do nothing without provoking an immediate internal crisis and the end of his government – the conservatives in his party and the Nationals would revolt if he tried any course other than a plebiscite.

If Dutton had wanted to see an early collapse of Turnbull’s prime ministership, he simply would have stayed mum. Instead, he helped solve the crisis of August 2017. He pushed for the lateral solution of a postal plebiscite, which could be held without need for parliamentary approval.

He persuaded Turnbull of this course over a couple of dinners at the Lodge and then advocated it forcefully within the government. It delivered Turnbull victory from the jaws of defeat on one of the most fraught issues of the time. Dutton and the conservative West Australian senator Mathias Cormann emerged as an unlikely praetorian guard for Turnbull, protecting a progressive prime minister from attack from his right flank.

One of the younger conservative Liberals explained that ‘‘most of us didn’t have the standing to pick up the phone and blast Turnbull directly and we wanted Peter and Mathias to do it for us, but instead they’d defend him. It was very irritating for us.’’

The pair gave Turnbull honest advice and helped him solve political problems. Like a joining of the Terminator and the Enforcer, Cormann and Dutton developed the habit of going for early walks around Canberra to discuss their work.

Cormann was especially deft at negotiating government legislation through a prickly Senate.

Turnbull appreciated and admired Cormann’s judgment and skill. The prime minister pushed him forward for media appearances as one of the government’s most reliable spokespeople. Any reservations about his intimidating Belgian accent were trumped by his ability to stay calm and ‘‘on message’’.

The relationship grew so close that Turnbull and Cormann even talked about going into business together after they’d finished in politics.

One of the greatest reasons that Turnbull came to trust Dutton and Cormann? His dealings with them never leaked. Turnbull relied on them more heavily as the months passed. If he had heard their frank assessments of him, he would not have been so confident.

An unflattering Cormann refrain about his prime minister, whenever the question of Turnbull’s beliefs and convictions came up: ‘‘We don’t know what Malcolm believes in.’’

One of Dutton’s main frustrations was that Turnbull was ‘‘hopeless at politics’’. His 2016 election was ‘‘the worst campaign I have ever seen’’. He was incapable of connecting with the conservative half of his own party. When Turnbull would make his proud boast that he ran ‘‘a good, orderly cabinet government’’, Dutton would make the aside: ‘‘That’ll get the base fired up.’’

As Turnbull put more and more trust in the pair he considered to be his most constant counsellors, he withdrew trust from his deputy, Julie Bishop, in equal measure. He consulted her less. He became reluctant to support her on even the smallest matters.

Seating arrangements, for instance. The deputy leader had always sat just behind the leader in the Parliament, meaning he or she would be prominently in view of the TV cameras. At one point Christopher Pyne decided he wanted to have more TV time and asked for Bishop’s spot. When Turnbull agreed, Bishop was unimpressed.

‘‘Just stand up to him,’’ she told Turnbull. Bishop was shuffled aside so Pyne could preen. Turnbull’s reliance on Dutton meant the immigration minister won all the powers he sought. Turnbull agreed to give him expanded legislative powers over citizenship and security, and even power over other ministers and their powers.

In a protracted power struggle to create his new super-ministry of Home Affairs, Dutton prevailed over four other ministers and the objections of all their departments. Turnbull described the centralisation of power under Dutton as ‘‘the most significant reform of Australia’s national intelligence and domestic security arrangements and their oversight in more than 40 years’’.

Dutton also built his standing among the party’s conservatives by signalling that he shared their values on a range of issues.

On the political correctness of the gender doctrines of the socalled ‘‘safe schools’’ program, on the rape of children in Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, on the UN’s compact on immigration, on funding for Catholic schools, on African ‘‘crime gangs’’ in Melbourne, Dutton would throw some handfuls of ideological red meat to right-wing media outlets to get the party’s conservative membership into a frenzy.

It was a knack Turnbull didn’t possess and didn’t want to cultivate. For every admirer Dutton won among the party’s conservative branches, he alienated thousands in the wider electorate. In polls asking voters to name their favoured Liberal leader, Bishop and Turnbull always led, while Dutton never cracked double-digits.

He told himself there was time to broaden his public appeal once he became leader. His followers, taking heart from his occasional flashes of humour behind closed doors, believed. For instance, Dutton would sometimes tease Pyne privately for his camp manner and love of the limelight.

‘‘Mate, you should buy the Dame Edna Everage franchise when Barry Humphries is finished with it,’’ he told Pyne. ‘‘You’d be perfect for it.’’

Pyne would just laugh.

But in the meantime, Dutton was riding a powerful wave of right-wing self-righteousness. And loving it.

In April last year, Turnbull failed the test he’d set for his predecessor. When he challenged Abbott, Turnbull condemned him for ‘‘losing’’ 30 Newspolls in a row. By his own criterion, Turnbull was no longer fit to be leader. No one in the party would need to justify challenging Turnbull. It was open season.

And it was in April that Dutton stated his ambition plainly: ‘‘Of course I want to be prime minister,’’ he told The Guardian. ‘‘That’s an ambition long held and is only realistic if stars align and an opportunity comes up.’’

Privately, he consulted his own star charts and decided that same month that they were very likely to align by the end of the year. Unless there was some miraculous Turnbull turnaround, Dutton would strike.

Eventually, other conservatives, such as Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, started urging Turnbull to anoint Dutton as his deputy. It was his best chance of survival, they told him. That would involve, of course, disowning Bishop.

By early last year, Bishop was confident that Dutton was running for the leadership, figuratively and literally. No longer content to go on early walks with his fellow praetorian guard Cormann, Dutton had taken up jogging.

She was right, and Dutton’s gains were, again, her losses.

In the final meeting of the cabinet’s national security committee under Turnbull, there were four major agenda items where the Home Affairs Minister and the foreign affairs minister took opposing positions.

This was the meeting, in August, where Australia was to decide a threshold question on the building of its 5G telecommunications network, the hyperconnected system to sustain the so-called ‘‘internet of things’’: would China’s giant Huawei be permitted some involvement, or banned?

Dutton prevailed on all four matters, including the Huawei decision, an issue that turns out to be a great geopolitical dividing line between a rampant China and a defensive United States.

Where Bishop wanted to explore the options the British are employing to allow Huawei some involvement, Dutton and the intelligence agencies took an absolutist line. Any Huawei participation opened Australia’s vital infrastructure to the potential shutdown by Huawei under orders from the Chinese Communist Party.

The prime minister concurred with his Home Affairs Minister.

Dutton left the cabinet room with a victor’s swagger; Bishop, humiliated, was on the verge of tears. Out on the backbench, Abbott was raging publicly against Turnbull over energy and climate change. Still. And publicly endorsing Dutton as ‘‘the outstanding minister of the Turnbull government’’.

He’d make a fine prime minister, said the former leader. Who was whose stalking horse now?

Dutton and Mathias Cormann (pictured) emerged as an unlikely praetorian guard for Turnbull.

TOMORROW

The final days of the Turnbull government