‘Green’ aluminium draws top-grade ore

Versatile and lightweight, aluminium should be at the forefront of global efforts to curtail carbon emissions. But producing the metal – often referred to as ‘solid electricity’ – is a high-energy process that currently relies on fossil fuel sources.

As with other sectors with a high-emission footprint, the game is rapidly changing for the smelters as the leading producing nations raise the bar on environmental standards.

The Chinese government is speculated to be limiting low-grade bauxite imports, while the country’s two leading producers, Chalco and China Hongqiao, are already leading the way on reducing emissions.

Elsewhere, Russia’s Rusal and Alcoa of the US are promoting zero-carbon aluminium products.

Aluminium is produced by refining alumina which, in turn, is produced from the raw material, bauxite. About four tonnes of bauxite are required to make two tonnes of alumina, while two tonnes of alumina are required for one tonne of aluminium.

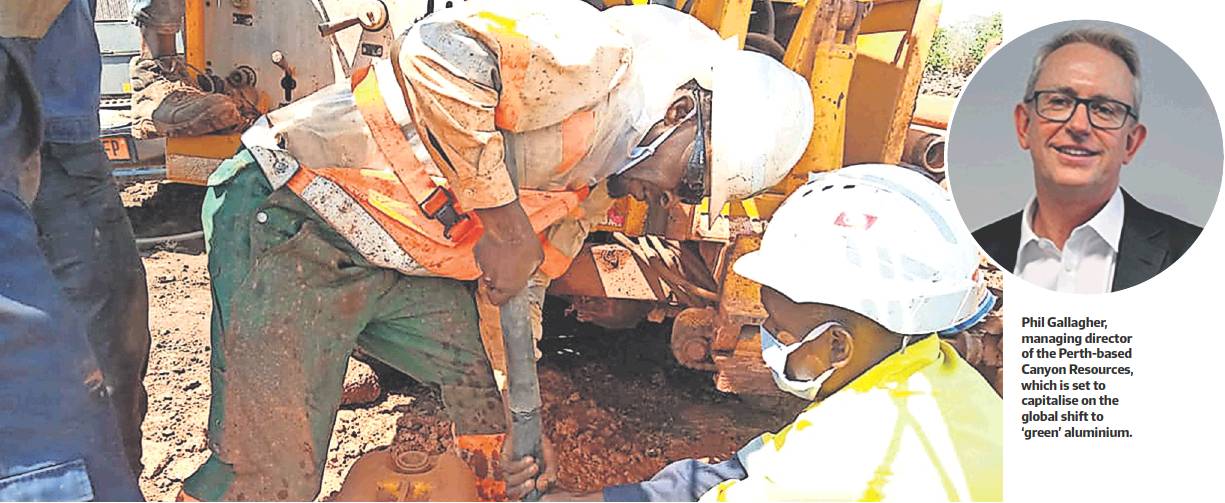

“In this new world of ‘green’ aluminium, one of the greener things the refiners can do is use high-grade bauxite because it takes less energy and less caustic soda to produce the alumina, with less waste material,” says Phil Gallagher, managing director of the Perth-based, Africa-focused Canyon Resources.

This low-emissions imperative puts Canyon in an ideal position as it moves to develop its fully owned flagship asset, the Minim Martap bauxite project in central Cameroon.

Gallagher describes Minim Martap as “the best bauxite deposit in the world, bar none” and it’s no idle boast: the bauxite grades rival those of the world’s great bauxite provinces such as Cape York, Guinea and Brazil.

Minim Martap consists of gibbsite, the most desirable of the three main bauxite ores because it can be refined at a lower temperature and is low in reactive silica content.

“We have the only project with both substantial grades outside of Guinea, where grades are declining,” he says.

Canyon envisages a multi-phased development of the project, which would be the first commercial mine of any type for the developing West African nation.

The company’s prefeasibility study outlines the base case of a simple direct-shipping operation based on output of 4.9 million tonnes a year over a 20-year mine life.

This assumes pre-production capital expenditure of a modest $US119 million ($165 million), implying a post-tax net present value of $US291 million and an internal rate of return of 37 per cent.

Minim Martap boasts a formal (JORC-compliant) resource of 1 billion tonnes, grading 45.3 per cent aluminium oxide and only 2.7 per cent silica (which can be hard to separate).

“We have a billion-tonne resource and we haven’t even drilled half the area yet,” Gallagher says. “We could keep drilling and prove out 2 billion tonnes, but it comes down to, ‘How many years of mining do we need to prove’?”

As with any greenfields project, access to infrastructure is just as crucial as having viable grades and good metallurgy.

Conveniently, Minim Martap is about 50 kilometres from an existing rail line linking the region to the existing Atlantic port of Douala.

“The unique thing with Cameroon is they have existing rail infrastructure that just happens to go past our project,” Gallagher says.

While the project is 800 kilometres from port, the higher transport costs are obviated by the superior quality of the ore, which means it does not need to be beneficiated before being shipped.

The second phase of the project potentially involves directing higher tonnages to the deepwater – but less developed – port of Kribi, which is subject to a government-backed upgrade.

Canyon is in the process of submitting its mining permit application, with approval expected as early as the December quarter. A bankable feasibility study is due to be completed in the current quarter.

A crucial part of the approvals jigsaw, a formal Environmental Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) was submitted by the company to the Cameroon Ministry of Mines in early June.

In other jurisdictions such as Guinea and Jamaica, bauxite mining has created civil unrest often resulting in mining disruptions.

Prepared by an independent expert, Environment and Social Sustainability, the report recommended that Canyon’s project proceed given its significant benefits to the region and the lack of significant adverse effects.

Meanwhile, Canyon is also working on binding offtake and rail and port access agreements as well as funding options including potential public-private-partnerships.

Canyon listed on the ASX in 2010 with an initial Australian and West African gold focus. But its attention turned to bauxite after the Cameroon government granted Canyon the permit for Minim Martap – as well as the adjacent Makan and Ngouandal deposits – in 2018.

“For years, we had been chasing the government to grant it to us because it’s such an amazing project,” says Gallagher, who lived in Cameroon before the pandemic and is highly familiar with the nation’s regulatory processes.

Gallagher says bauxite is less understood by investors than gold or iron ore and is “definitely less sexy”. But this perception is rapidly changing, with the European Union last year designating bauxite as a ‘critical mineral’ given the dominance of Chinese users.

“Green aluminium is very much the focus in the infrastructure and car building sectors globally,” Gallagher says.

“Recently, we have fielded some really interesting approaches from large organisations in the sector, whereas a couple of years ago we had to seek them out.”

For Canyon investors, the financial rewards could come sooner than they expect: Foster Stockbroking forecasts first revenue from the 2023-24 year, generating a net profit of $11 million.