State in crisis: who’s in charge?

INSIDE STORY

Chip Le Grand

Chief reporter

Victoria’s most senior public servant was ebullient. Winter had arrived, COVID-19 had all but disappeared and Chris Eccles, the man in charge of Daniel Andrews’ Department of Premier and Cabinet, was humming with enthusiasm about the possibilities that lay ahead.

In a relaxed, expansive interview at the start of June, Mr Eccles spoke of a ‘‘moral purpose’’ and the need to ‘‘crash through’’. The virus was thought to be contained and hubris had infected the conversation.

‘‘I think the response to date has shown an increase in confidence and trust,’’ Mr Eccles told his interviewer. ‘‘And with that confidence and trust, I think comes licence. I think there is now the greatest opportunity in my time as a career public servant for that licence to shape the economy, service systems and more generally create a more equitable, inclusive and progressive society.’’

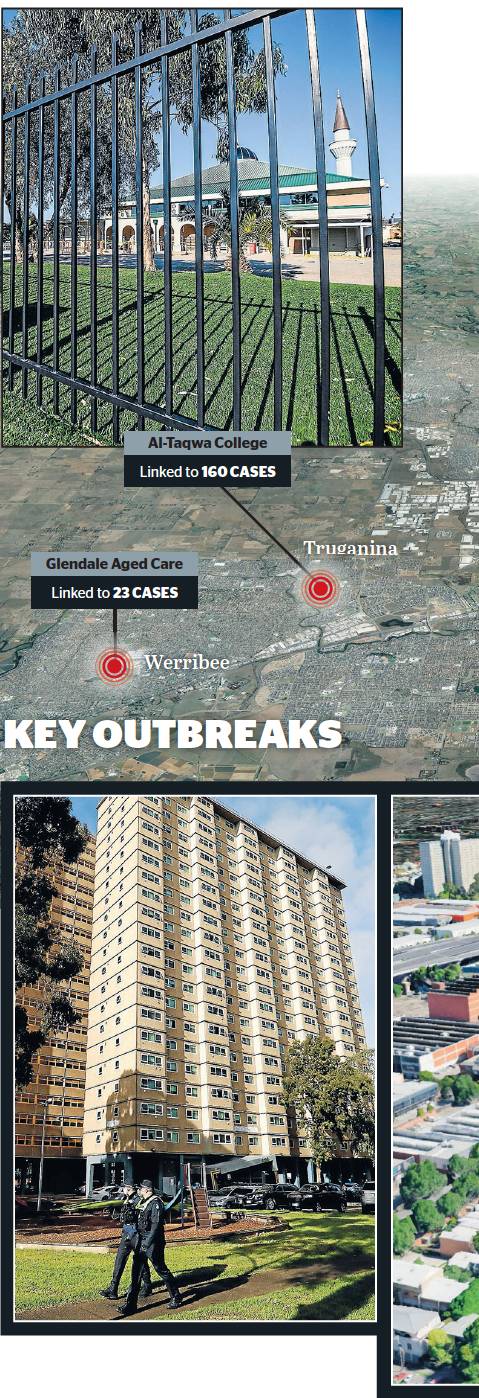

Six weeks later, Victoria is engulfed in a second wave of infections – daily cases are surging in numbers not seen previously in Australia throughout the pandemic, Melbourne’s hospital wards are filling and, starting on Monday, retired judge Jennifer Coate will open a public examination into the quarantine failure which allowed COVID-19 off the leash.

Confidence and trust generated by the Victorian government’s early success in bringing the virus under control has been eroded by frustration, dismay and in some cases, anger that, having emerged briefly into the light, we are back in the long, dark tunnel of the pandemic.

The economic cost, according to Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, is $1 billion for every additional week Australia’s second largest city spends in lockdown. The human toll, in disease, family dislocation and death, will not be known for months.

Yet, despite these catastrophic consequences, no one has accepted responsibility for what went wrong. As one former senior public servant put it: ‘‘This is the biggest bureaucratic and political f--- up with the most dire consequences probably in Victorian history but there has been absolutely no accountability.’’

The terms of reference of the Coate inquiry include the decisions and actions of government agencies, hotel operations and private security companies, resulting in returned travellers passing the virus on to quarantine guards who, unwittingly, took it home to their families and spread it through their communities.

Its intent will become clearer on Monday when Justice Coate, a retired Country Court judge and former president of the Children’s Court of Victoria and counsel assisting Tony Neal, QC, tender their opening statements.

The inquiry, due to report by September 25, is constrained by narrow terms of reference and a short time frame. In an unusual arrangement, Mr Neal will be instructed by lawyers provided by the Victorian Government Solicitor’s Office, after Justine Coate satisfied herself there was no conflict of interest in government lawyers interrogating government officials on matters of government policy.

As a starting point, it must answer a question that has plagued the entire Victorian response to the pandemic – who exactly is in charge?

Mr Andrews has repeatedly said that, ultimately, he is accountable for the decisions of his government. Mr Eccles’ description of his new bureaucratic structure, in his interview with Institute of Public Administration president Gordon de Brouwer, suggests this is not a platitude.

As the pandemic crisis has unfolded, the bureaucracy was reorganised into what Mr Eccles called ‘‘missions’’: health, economic and social imperatives framed in response to the pandemic. These include the health emergency, business continuity and the eventual economic recovery and restoration of government services.

Each mission is led by a departmental secretary who, according to Mr Eccles, is ‘‘directly accountable to the Premier’’. This has further centralised decision making in the Premier’s office and makes traditional lines of Westminister accountability – where ministers carry the political can for anything that goes wrong in their departments – difficult to apply.

Sources experienced in emergency management say that in Victoria, a bigger problem lies beneath the political tier. For any crisis response to be effective, there needs to be a chief operator – a senior civil servant or expert seconded for the purpose – who is responsible for managing everything. In Victoria, it is not apparent who this is.

Mr Andrews this week described the virus as a cunning and wicked enemy. Who is commanding the state’s defences against it?

Is it Brett Sutton, the Chief Health Officer who, under Victoria’s rolling state of emergency in force since March, has extraordinary powers to order the closure of businesses and direct people to stay home?

He has already disavowed the decision to hire private security guards to staff the quarantine hotels, saying it was neither his idea nor one he supported. Government sources confirmed the Professor Sutton has a largely advisory role.

Is it his boss, Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Kym Peake? Is it Victoria’s Emergency Management Commissioner Andrew Crisp?

Under the Emergency Management Act, Mr Crisp has responsibility for co-ordinating the response to and recovery from any major emergency. In practice, it is unclear where Emergency Management Victoria fits into the pandemic response.

Last month a ‘‘high priority’’ request to the federal government for 850 Australian Defence Force personnel to bolster the state’s hotel quarantine arrangements was personally signed by Mr Crisp and approved by the ADF. Within hours of Canberra agreeing to the request, it was rescinded by the Victorian government.

John Cantwell, a retired majorgeneral in the army who was seconded to the Brumby government to lead the recovery from the Black Saturday bushfires, says he cannot tell who is running Victoria’s response.

‘‘My role was to be the coordinator, the facilitator and the front man for the whole response,’’ he says. ‘‘It had a straight echo from my military experience, where someone has to be responsible. You can’t divvy it up and hope they will talk and share and co-ordinate. It just doesn’t happen.

‘‘As an outsider looking in, I don’t get a sense there is a single minister responsible for this. And even within their realms of responsibility, my perception is there has been a bit of shirking of responsibility by significant players. I have heard no one talk about a single entity that coordinates this. Perhaps they are sight unseen.’’

When asked this question by The Age, a government spokesperson said: ‘‘There are thousands of people working hard every day to save lives and support Victorians as we fight this deadly pandemic.’’

Career bureaucrats familiar with emergency management do not doubt this but say there is a central piece missing. ‘‘You have got to have someone who is unambiguously in charge of everything the government is trying to do,’’ explains one. ‘‘If there is no one person, that would normally be regarded as a recipe for dropping things, being slow to respond and having mistakes made.’’

Within Labor, there are also growing concerns. ‘‘What we are seeing is an absolute failure of emergency management,’’ one party insider says. ‘‘The Premier himself calls it a public health bushfire but there has been no central coordination.’’

Prime Minister Scott Morrison is publicly backing the Victorian response. Privately, the federal government is perturbed about what is happening in Victoria, where earlier in the pandemic, the state government was reluctant to accept Canberra’s help. That help has now arrived in the form of deputy chief health officers from Queensland and Western Australia, the Commonwealth’s Chief Nurse, Allison McMillan, and a contingent of 1000 ADF troops that Andrews agreed to this week.

David Davis, the minister for health under the Baillieu and Napthine governments, says the pandemic has exposed structural deficiencies in the Department of Health and Human Services created, in part, by the government’s decision to merge two separate bureaucracies back into a single mega department.

He believes the department is simply too big and complex to manage and attempts to do so have been hampered by the Premier’s tendency to direct its operations through his own office.

‘‘The department and minister have comprehensively mismanaged the COVID response,’’ Davis says.

Others who have worked within DHHS defend its structure and point out that, in a public health crisis, organisational charts have little relevance to how decisions are made, invariably in very quick time, when confronting changed circumstances on the ground.

In times of peace, let alone a pandemic, it would be a difficult task to track decision making and accountability through the reporting lines of the sprawling DHHS, an organisation with a $27 billion budget and more than 11,000 employees.

Ms Peake, a smart, talented bureaucrat appointed to the role with limited management experience, is normally sandwiched between five ministers she answers to and 10 deputy secretaries who report to her.

Professor Lindsay Grayson, an infectious diseases expert, wrote last week that Victoria’s health department was ‘‘one of the worstfunded and dysfunctionally organised’’ in the nation.

Whether Victoria is paying a terrible cost for that dysfunction is now a matter of vital importance.