We can’t escape a carbon tax, which is good news, not bad

COMMENT

Ross Gittins

When economists are at their best, they speak truth to power. And that’s just what two of our best economists, Professor Ross Garnaut and Rod Sims, did this week. In their own polite way, they spoke out against the blatant self-interest of our (largely foreignowned) fossil fuel industry.

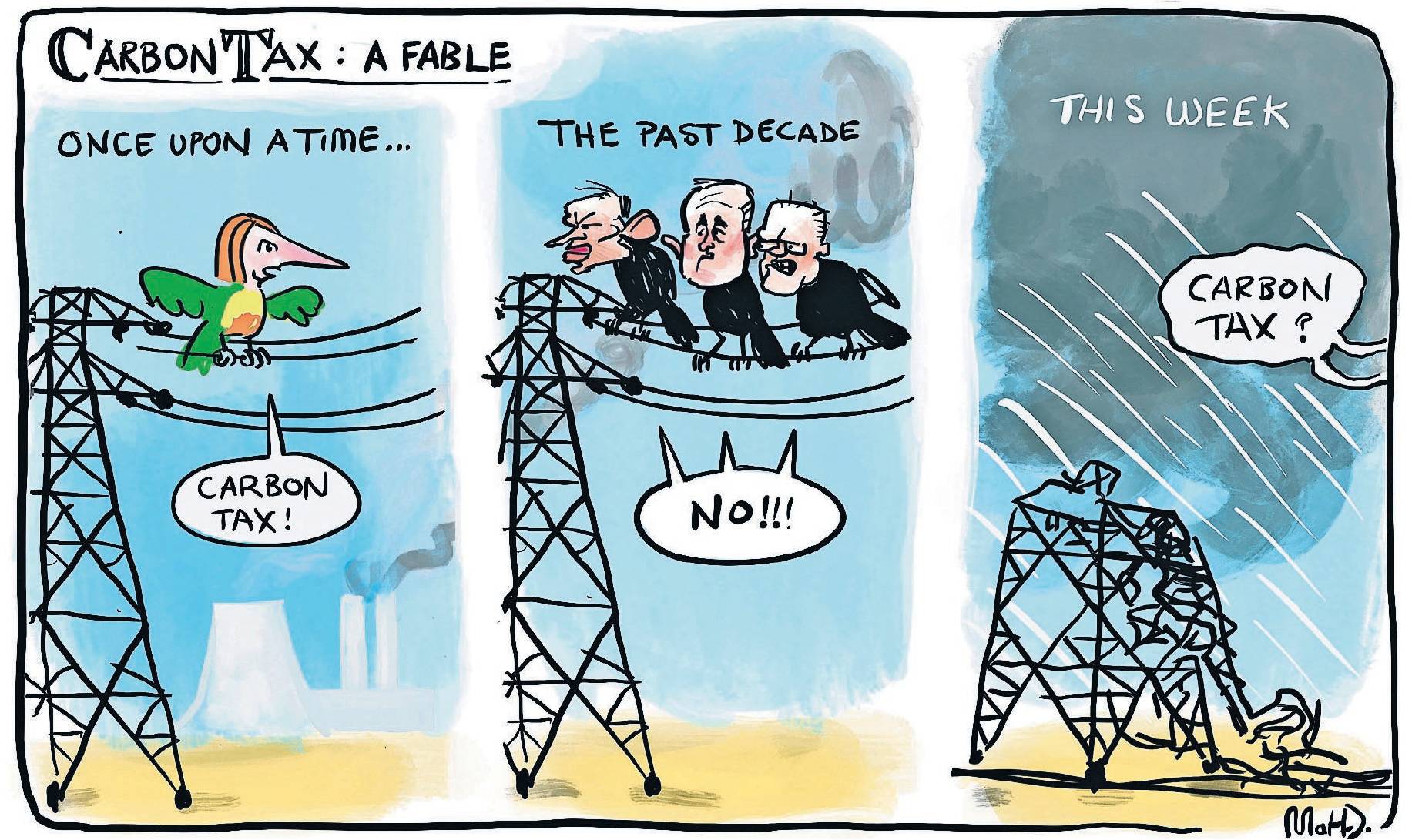

They sought to counter the decade of damage done by the former federal Liberal government which, for shortsighted political gain, engaged in populist demonisation of Julia Gillard’s carbon tax. And, by their willingness to call for a new ‘‘carbon solution levy’’, they shamed the present Labor government, which dare not even mention a carbon price and isn’t game to take more than baby steps in the right direction, for fear of what Peter Dutton might say.

But the two men’s message is actually far more positive than that. In launching a new think tank, the Superpower Institute, they pursue Garnaut’s vision of how we can turn the threat of climate change into an opportunity to revitalise our economy, raising our productivity and our living standards.

Sims, former boss of the competition watchdog, says that, following a decade of stagnant production per person, real wages and living standards, Australia’s full participation in the world’s move to achieve net zero global emissions is the only credible path to restoring productivity improvement and rising living standards.

Climate change is a threat to our climate, obviously. But it’s also a threat to our livelihood because Australia is one of the world’s largest exporters of fossil fuels. Garnaut points out that, as the rest of the world moves to renewables, two of our three largest export industries will phase out.

This will send our productivity backwards, he notes – as all the bigbusiness people reading us lectures about productivity never do.

The good news, however, is that ‘‘putting Australia back on a path to rising productivity and living standards doesn’t mean going back to the way things were’’. It’s now clear that ‘‘Australia’s advantages in the emerging zerocarbon world economy are so large that they define the most credible path to restoration of growth in Australian living standards.’’

Garnaut says that ‘‘In designing policies to secure our own decarbonisation, we now have to give a large place to Australia’s opportunity to be the renewable energy superpower of the zerocarbon world economy.’’

Other countries do not share our natural endowments of wind and solar energy resources, land to deploy them, as well as land to grow ‘‘biomass’’ – plant material – sustainably as an alternative to petroleum and coal for the manufacture of chemicals.

From a cost perspective, we are the natural location to produce a substantial proportion of the products presently made with large carbon emissions in North-East Asia and Europe.

The Superpower Institute champions a ‘‘market-based’’ solution to the climate challenge. We shouldn’t be following the Americans by funding the transition from budget deficits, nor become inward looking and protectionist.

Rather, everything that can be left to competitive markets should be, while everything that only governments can do – providing ‘‘public goods’’ and regulating natural monopolies – should be done by the government.

Sims notes a truth that, since Tony Abbott’s successful demonisation of the carbon tax, neither side of politics wants to acknowledge that markets only work effectively if firms are required to pay the costs that their activities impose on others and, on the other hand, if firms are rewarded for the benefits their activities confer on others.

When the producers of fossil fuels don’t bear the cost of the damage their emissions of greenhouse gasses do to the climate, and the producers of renewable energy don’t enjoy the monetary benefit of not damaging the environment, these two ‘‘externalities’’ – one bad, the other good – constitute ‘‘market failure’’.

And the way to make the market work as it should is for the government to use some kind of ‘‘price on carbon’’ – whether a literal tax on carbon, or its close cousin, an emissions trading scheme – to internalise those two externalities to the prices paid by fossil fuel producers and received by renewables producers.

The price on carbon that Garnaut and Sims want, their ‘‘carbon solution levy’’, would be imposed on all emissions from Australian produced fossil fuel (whether those emissions occurred here or in the country that imported the fuel from us) and from any fossil fuel we imported.

Only about 100 businesses would pay the levy directly, though they would pass it on to their customers, of course. It would be levied at the rate of recent carbon emission permits in the European Union’s emissions trading scheme.

Imposing the levy on all our exports of fossil fuel, rather than just our own emissions, makes the scheme far bigger that the one Abbott scuttled in 2014. It would raise about $100 billion a year.

But it’s bigger to take account of the Europeans’ ‘‘carbon border adjustment mechanism’’ which, from 2026, will impose a tax on all fossil fuels imported from Australia that haven’t already been taxed.

Get it? If we don’t tax our fossil fuel exports, the Europeans or some other government will do it for us – and keep the proceeds.

What will we do with the proceeds of our levy? Most of them will go to a ‘‘superpower innovation scheme’’ that makes grants to support early investors in each of our new, green export industries. In this way it will lower the prices of carbon-free steel, aluminium and other products, helping them compete against the equivalent polluting products. The positive externality internalised.

Garnaut says we need to have the new levy introduced by 2031 at the latest. But the earlier it can be done, the more of the levy’s proceeds can be used to provide cost-of-living relief of, say $300 a year, to every household and business, as well as fully compensating for the levy’s effect on electricity prices.

Thank heavens some of our economists are working on smart ways to fix our problems while our politicians play political games.